Useful Theories of Change

Guidance and resources on accessible, useful, and usable Theories of Change.

What are they?

Useful Theories of Change are as their name suggests. Useful.

Traditional Theory of Change (ToC) models frequently miss the mark. They feel uncomfortable.

How many times have you been in a ToC workshop and had these kinds of discussions or situations:

(i) ‘But is this an output or an outcome?’ ‘Both and neither’ ‘Maybe we need to include ‘intermediary outcomes’?’

(ii) mass confusion over the definitions of an output vs an outcome

(iii) a team who does not have English as their first language, or an interpretor, struggling to translate ‘output’ or ‘outcome’

(iv) a bunch of boxes and arrows that doesn’t really feel relevant to the programme

(v) someone telling you this is why they ‘don’t really believe in/like theories of change’

I think we have all been there. That is because traditional ToCs are not really theories of change, and the words ‘output’ and ‘outcome’ fail to really capture what is going on when we are trying to change something (and therefore are so hard to translate). Ultimately, these models tend to focus us on entirely the wrong thing as we fall into the is-it-an-output-or-outcome tug of war and fail to actually think about what change looks like.

Ultimately, the real danger of this model is that it ends up trying to simplify highly complex change processes into something neat and tidy… which is simply not realistic, and in reality ignores the complexity.

This is a problem for a number of reasons, not least that this means you don’t actually think about or articulate the mechanisms of change. This is a problem for your programme design, as you haven’t really put pen to paper in terms of your hypothesis for positive change. It is a problem for your MEL systems as they cannot appropriately measure change if it is not articulated. It is a problem for risk management, as you cannot identify causal risks to a programme if you haven’t articulated the hows and whys of change.

As Patricia Rodgers tells us in her infamous paper (I know, I quote this ad nauseum but it is simply because she is right!), we need to stop applying simple models to complex situations.1 This segment is about a better model. As with some of my pages, I am not sharing anything new here. Folk just seem to like the way I talk about things in plain English and I want to take the opportunity to draw attention to this incredible model.

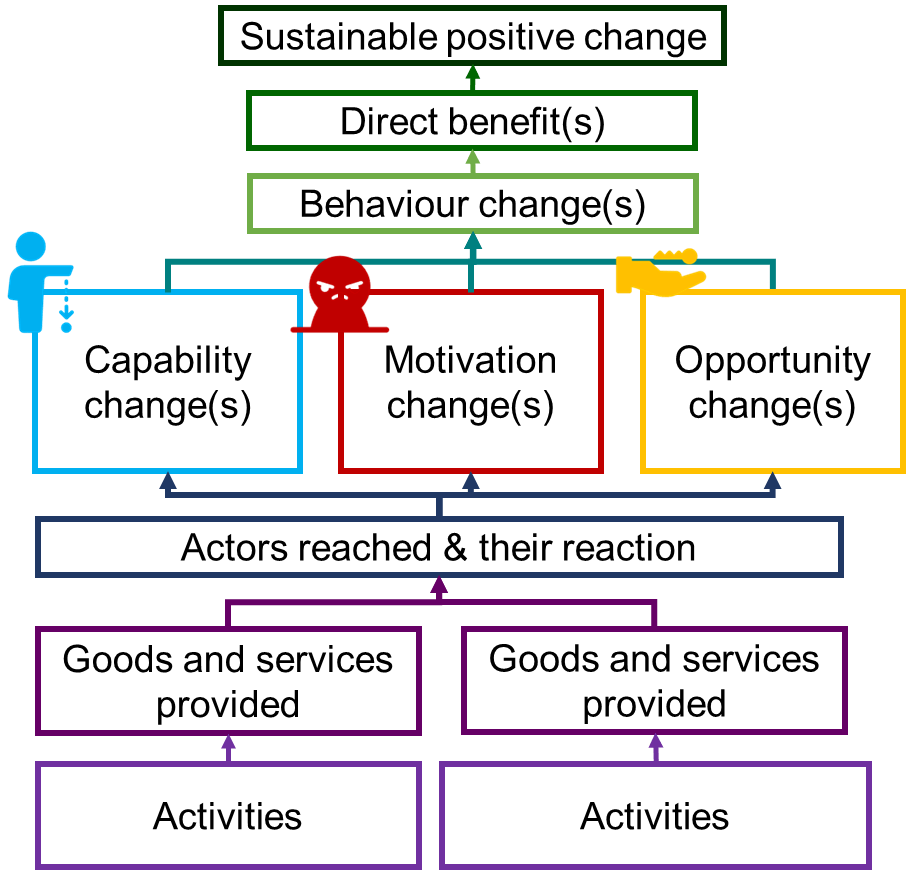

Useful ToCs (UToCs), as pioneered by John Mayne in 2015, actually describe change. [2] They do away with confusing, untranslatable, and out-of-date language around ‘outputs’ and ‘outcomes’ (you can read my blog about why I feel so strongly about this) and use plain language to describe the pathway that takes you from point A to point B.

Ultimately, when trying to change things, you do some stuff, which produces some kind of good and/or service, which reaches the right people who react in change-conducive ways, who then gain some kind of capabilities, opportunities and motivations (click here for more on this) which then leads to behaviour change. That behaviour change (either individual, group, organisational, or systemic) will allow a direct benefit to occur, which contributes to what maybe calls a ‘wellbeing change’. Personally, I find it easier to frame ‘wellbeing change’ as a ‘sustainable positive change’ to be more inclusive of non-development style programming.

It is, of course, more complex than that.

- Firstly, there are assumptions that can be teased out at every level (see Mayne’s example below) so that you are clearer on what your causal assumptions are at each stage. This is really important for causal risk identification!

- Secondly, you will have feedback loops and horizontal causation present, but I am keeping visuals simple for now.

- Thirdly, you will need to account for external influences and unanticipated results of your intervention (see Mayne’s example below). Personally, I also consider an additional category of ‘indirect results’, as often we have indirect negative or positive results that we can anticipate and may actively want. An example of these are Secondary Benefits, or things like Political Access and Influence for those operating in the FCDO space. For others, examples of these might be an increase in women’s empowerment as an indirect result of people-centred justice programming: the goal is to bring about people-centred justice institutions, but by doing so we make justice more accessible to women. Women will then use it more, and be more empowered. This is a result that we like and see as positive, but it is not what we are aiming at. As such, it is an indirect, positive, result of the programme.

- Finally, you can better nest theories of change. Nesting is when you might need to include sub-theories, or theories of action, to further explain other causal connections. For example, you might have a regional theory of change for a multi-country programme, and then nest theories of change for each country into that regional one. Like a Matryoshka doll.

Why does this matter? Well, all of this is very important for planning how you create change, as well as how you measure it and manage risk. The Useful model makes all of this much easier to identify and pull out, because we are using accessible language and a more realistic representation of change. To illustrate, see Mayne’s example below from his paper:

While this can of course be wrapped in narrative and include more detail, the point is that it is a MUCH better illustration of what the programme is trying to do, what it is assuming, what might happen indirectly, and what external effects it is vulnerable to.

To give another example: you develop a training programme, which produces workshops and training materials, which reaches the high-flying journalists that write about governance abuses (in country x). These journalists attend the training and listen, rather than falling asleep, and gain skills in quality journalism and confidence to trust their instincts and try different approaches. These capabilities and motivations mean that instead of writing pieces that get lost or ignored, they write effective journalism that attracts attention. This behaviour means that the government is publicly shamed for bad behaviour, which contributes to the government reducing its civil liberty violations.

That’s far more change-friendly and intuitive than: deliver training programme -> policy implemented better -> Government of Uzbekistan’s transformational plan rolled out.

The crucial parts of these ToCs is that they really highlight behaviour change, which is a crucial hinge point of your programme. Behaviour change is where your programme stops being able to directly affect things and hope that change occurs from your actions.

I see it as like going bowling. You pick a ball of the right weight for you, you put on the right shoes, you line yourself up and throw as straight and as hard as you can to knock over all the pins. However, you cannot control whether it actually does! You just have to hope that (i) you did all the right things to allow that, and (ii) that nothing strange happens like a child running onto your lane, or even something positive like a sudden gust of wind blowing over more pins for you.

It’s where implementation hands over to theory, and you hope that you understood the context and got your assumptions right such that others start to do things differently.

Importantly, you can also use UToCs! They’re powerful aids to fuelling a robust, evidence-informed causal risk matrix and programme management structures. This is because we are explicitly pulling out far more assumptions, but are also empowered to better identify external effects and indirect results. They’re also far easier to measure because they better explain change, and so form the foundations for powerful results frameworks.

[1] Rogers, P. J. (2008). Using Programme Theory to Evaluate Complicated and Complex Aspects of Interventions. Evaluation, 14(1), 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389007084674

[2] Mayne, J., Useful Theories of Change, Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, 2015

A traditional model

How do I do it?

UToCs are intuitive and therefore really easy to build out: everyone knows what a good or service might be, whereas few are usually clear on what the outputs of a programme may be. I have yet to have trainees, team members, or fledlings who have found a UToC difficult to build. You can design these as you would a traditional ToC.

What I find quite helpful to get these things going is to use an elevator pitch exercise. I ask teams the following: imagine you are in an elevator with me and I am getting off in 3 floors. How and what is your programme doing? Why does that matter?

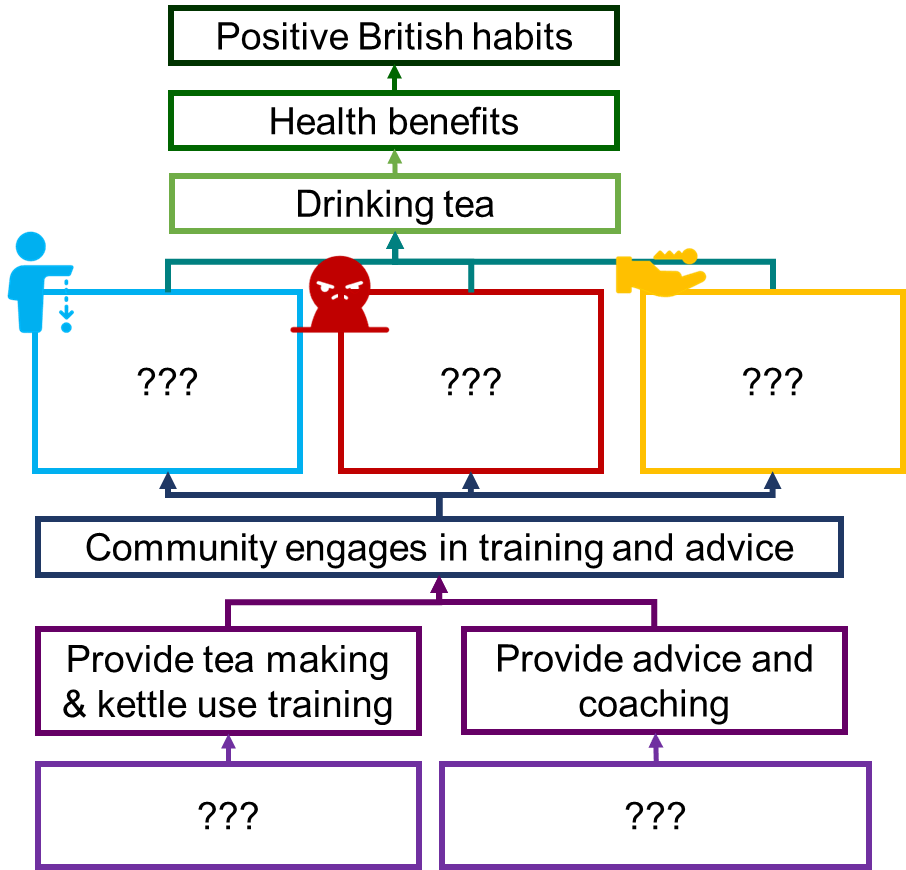

This formula is very helpful for giving foundations for a UToC, as you might get things like: Through advisory support, training, and coaching, we are trying to help a small community to drink more tea. This is important because tea has health benefits, and represents positive British habits.

These give some building blocks, where ‘advisory support, training, and coaching’ form the goods and services being provided, ‘small community’ forms the reach, and ‘drink more tea’ represents a behaviour change. The health benefits of tea and positive British habits form direct benefits, or even possibly a sustainable positive change:

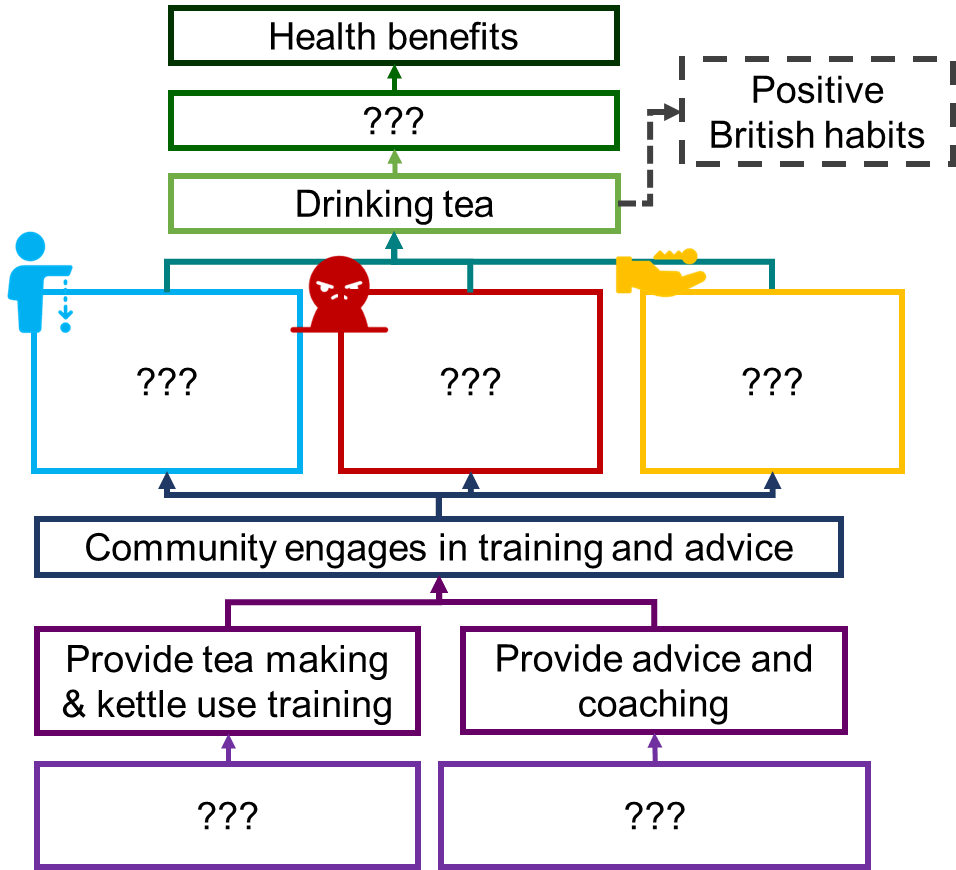

Equally, you might see the Positive British Habits as a Secondary Benefit (a form of indirect, but positive, causal effect of a change):

Either way, it has some holes, but it is a starter for ten. It is a lot easier to work with a skeleton than to start with a blank sheet of paper. I really recommend using that elevator pitch formula to get people going, and then you can start building up your UToC from there.

If feeling academically inclined, you can try out the John Mayne 2015 paper that I signposted above. It is really readable and inspiring! I can also suggest consultants who are very well versed in this model.