Complexity

How to recognise, and understand, complexity.

What is this?

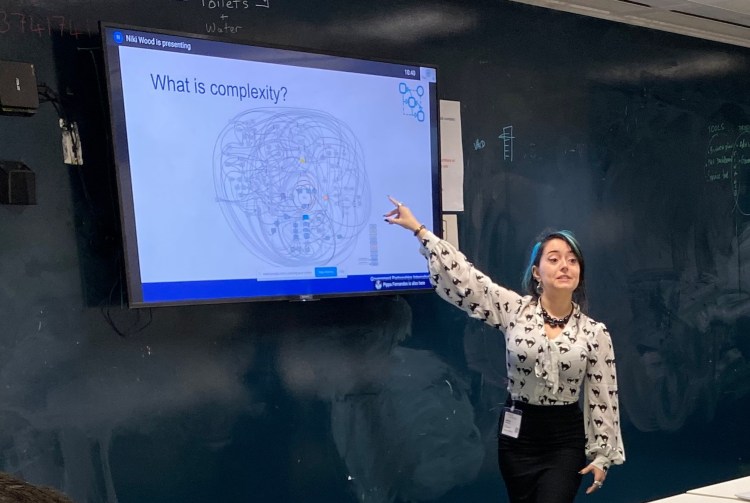

Complexity. It feels like a lot. When I ask the uninitiated what comes to mind when one hears the word ‘complexity’, I often get phrases like ‘a tangled mess’, ‘something with many components’ or even ‘something scary to address’. One even may imagine an image like this:

This is the Foresight Obesity System Map: a complexity map of the obesity ‘problem’ and all the relevant players in that informal and formal system. It’s not a bad representation of complexity in its formal definition, but it is a bit hard to swallow, and to interpret. It certainly looks complex! Paradoxically, complexity itself is a simple concept to grasp.

Nothing I have to say here is new, or different, mind you. Again, I have been interested in complex systems ever since I did a stint working in the Ministry of Housing in the UK and learned a lot from complexity scientists and systems thinkers. However, I have always been told the way I put things into plain language helps people and so I wanted to share those explanations here. Please do read the source materials that I cite, however.

Complexity itself feels fairly nebulous, but once understood it can change people’s ways of looking at and responding to challenges. Managing and responding to complexity demands different approaches and different methods. To paraphrase CECAN, complexity is present in many social and natural systems. It is present in nearly all of the major challenges we need to address as those who hope to create positive change in the world, and in most cases it is pivotal in accounting for the success or failure of interventions. Being honest about complexity and making it genuinely explicit is integral, as it means we design interventions to be sensitive to the scale and nature of that complexity. If we ignore it, we risk failure. Similarly, if we try to simplify it, we are honestly just ignoring it. Generally speaking, complexity does not pose new challenges to us, but it simply magnifies the ones we are already working with.

I always introduce complexity in contrast to things that are not, and (as is beloved or tedious to my programme teams, depending on how many times they’ve seen it) I always refer to the Patricia Rodgers example [1] that involves interpreting these situations through the analogy of cakes, rocket ships and babies (see below).

In essence, Rodgers tells us we usually find ourselves in one of three situations. Well, technically four, but the fourth situation is a chaotic one: it’s like a tornado, you just run away. Let’s avoid that one shall we? These three situations follow as so.

Simple situations, like baking a cake: you have a clear end result with a process that is predictable, and linear. This will not require much time, and won’t require too many resources or too much money. There are known knowns, and known unknowns. It is also repeatable: every time you follow that process, you’ll get the same cake (unless you make a mistake).

Complicated situations, like building a rocket: again you have a clear end result but this time the process is less straight-forward. You will need a lot more time, money, and resources. You will find it has has multiple causal pathways and varied TA interventions. There will be known knowns and known unknowns, and maybe an unknown unknown, but it will be surmountable. You might discover something doesn’t work and it requires a feedback loop to amend, but ultimately the process is still relatively linear. The whole thing can be repeated to get the same rocket ship if you have the right resources, time, and money available again.

Complex situations, like raising a child: anyone who has ever raised a child knows that you may have a good idea of what you want the end result to be, but there is no guarantee that you will get there. The end result is highly difficult to predict. The pathway is highly complex: you have to learn as you go, change strategy, and have multiple unknown unknowns. What works today will inexplicably stop working the next day, then miraculously work the day after. This process is highly unpredictable and vulnerable internally and externally: things will change within the process, but it is also highly hostage to environmental factors that will create unexpected effects. The entire process will have multiple feedback loops and will be heavily adaptive. Ultimately, much like raising a child, this cannot be repeated to get the same result. This is the domain development work usually finds itself in, domestic or international.

The important thing for us to understand, as we know from literature, is that when we are in a complex situation we are ultimately working with highly complex systems.

Complex systems are everywhere, and more often than not the kinds of positive change we are trying to make are interacting with them (and in particular complex behavioural systems). One of my favourite analogies for this is a hive of bees.

Hives of bees are highly complex systems. What we have here is a concept – the hive – which emerges from an arrangement of actors – the bees- who are behaving in certain ways. Each bee is engaging in a specific behaviour, but critically they not behaving in isolation. They are interacting with and reacting to the behaviour of the other bees. As such, they engage in individual behaviours but also reactive behaviours in response to those in proximity to them (who themselves are reacting to those in proximity to them and so on forming long causal behavioural chains). These additionally create heirarchies and ways of working but I shan’t get into that. Just focus on these interactive and individual behaviours for now.

However, that is not all that is going on. These individual and reactive behaviours are not happening in isolation either. They are also reacting to their immediate environment: to the weather, predators, obstacles, gravitational forces, magnetic fields, and so on. These environmental factors mean that each individual, as well as the collective whole, move and interact in certain ways that form a cohesive whole. This is most acutely seen when swarms of bees are flying: the beautiful (perhaps not so beautiful if you are not an insect fan) shape is formed by this combination of individual and reactive behaviours, as well as individual and collective response to the environment.

This is most acutely seen as well when humans come along and fiddle about with a hive. We have to enter very carefully, in certain ways, or you will case a disruption and throw the hive into chaos (see note above about chaotic situations).

Whenever we try to do something, we have to be like beekeepers: you have to enter slowly, carefully, with thought and in a way that works with the bees to yield the reward of honey. We have to work with that complex system to encourage honey-making, or we risk creating chaos.

[1] Rodgers, P., Using Programme Theory to Evaluate Complicated and Complex Aspects of Interventions, Evaluation, 2008

How do I recognise it?

Complexity should be recognisable the second you meet the conditions mentioned above under the ‘complex situation’ definition. However, there are roughly 11 features of complex systems as identified by bodies like CECAN (see above link, original features and technical explanations are theirs) that I’ve tried to re-explain in plain English below, with some rudimentary examples, as sometimes they can be hard to understand in their original explanatory form. These are helpful both in understanding exactly what you’re dealing with, as well as identifying whether you are working with a complex system or not. I also tend to run a ‘developmenty’ example through this so that we can see a single thread of how this works.

Adaptation:

The first feature of a complex system is that it adapts. This means that parts of the system – its components – are learning and evolving, and thus changing how the system responds.

An example of this can be seen in shoals of fish (another example of a system!). As light pollution has been creating more false illumination close to shores, shoals of fish have been changing the depths at which they have been swimming. As such, they have adapted to the increased light and are operating differently.

I’ll also be using a more ‘developmenty’ example with a case study. An example of adaptation would be that as the Programme Leaders in the Civil Society Organisation (CSO) in the made up land of Teraria have learned leadership skills, the CSO sees a shift in how it behaves: all voices start to be included rather than the voice at the top.

Emergence and self-organisation:

Complex systems see emergence and self-organisation. In plain English, this means that when the parts of the system (‘components’) interact, you see higher-level properties arise from their interaction. These properties will likely be new and unexpected properties, making them hard to predict: these are called ’emergent properties’.

Social norms are emergent properties of social systems. The self-organisation and interaction of components in our current social systems have led to an emergent property of serious and systemic inequality for those of underrepresented identities such as being disabled or being trans. The current shifts in that organisation and interaction (mass, global protest) could lead to changes in social and working practices with regard to these identities. These would be emergent properties of that movement, just as the shape and structure of the hive of bees is an emergent property of how they are interacting, moving, and arranging themselves.

In our case study, the problem of lack of effective delivery of programmes is an emergent property of the Programme Leaders (components) having low skills and failing to communicate (interaction), as well as the lack of procedure and process (affecting how they self-organise).

Unexpected indirect effects:

When interacting with complex systems, you will see unexpected indirect effects. What this means is that a change in one part of the system can lead to unexpected change in what seems like a remote part of it. This happens because there are long causal chains of interaction between components in that system, such that they are able to carry an effect far down the system; much like how a spider on one side of its web can feel a fly land on the other side because of the links of silk.

For example, in Sweden we have very generous parental leave policies. For example, since 2014, couples have been entitled to use 480 parental leave days up until the child turns 12 years old.3 This has been gender equitable, with equal amounts of leave available to fathers. This had an interesting causal effect, however: studies have shown a positive association between the father’s parental leave use and healthy behaviours, including decreased alcohol use and increased physical activity, as well as decreased mortality risks.3 As such, the change made had an unexpected, but positive, effect on fathers’ health.

In our Terarian CSO we saw that an increase in leadership, team-building and communication skills has led to reduced working hours in the CSO. This is due to more efficient working and awareness of other practices.

Feedback loops:

Complex systems will have multiple feedback loops present. What this means is that a result of a given event will then influence how the given event (when repeated) causes change. This can be direct or indirect, and can suppress or accelerate change.

An example of this is that when alcohol percentage was reduced in a Swedish national beer, people increased the amount of it that they drank: a negative feedback loop from an initial event of reduction aiming to reduce alcohol intake. Instead of drinking less alcohol, they ultimately drank the same amount, or even more, with additional calories to boot. As such, you can see how this is a negative feedback loop in terms of overall population health: alcohol percentage decreases -> population drinks more -> population calorie intake increases -> population health decreases.

In our Terarian CSO, when hierarchical and unempathetic leadership practices decreased, members had an increase in motivation and productivity: a positive feedback loop that reinforces the new approach to leading.

Levers and hubs:

Complex systems will always have levers and hubs. Levers and hubs are effectively the idea that certain parts of your system will have the power to change everything, or block change. This is a concept we are familiar with: many stories feature a silver bullet or a holy grail that can change the tide of time. This concept acknowleges that in complex systems, some components in the system have disproportionate influence over the whole due to the structure of their connections.

For example, a key individual in an organisation may be an obstacle to change due to veto powers, or a gatekeeper due to approval powers: for example, Donald Trump slowed change by suspending funding to bodies and organisations such as the WHO. As such, he was a lever, but one that could not be leveraged if one wanted to fund the WHO.

Aisara is a key lever in the CSO due to her stature and the degree of respect for her. If she starts doing something differently, others will follow suit.

Non-linearity:

Complex systems are rife with non-linearity. What this means is that unlike with cake-baking or rocket-ship-building, pathways aren’t linear. A small change could cause a huge result in one situation, but the same small change may lead to no change in another. Likewise a big change may have small results in a given context, yet that same big change could have a huge result in another.

For example, the population size of London rats didn’t increase dramatically during the covid lockdown, despite some of their predators decreasing and food sources increasing: people had more food waste from an increase in take-away consumption (and domestic bins are easier to access than heavier-duty restaurant bins), and people kept pets inside due to fear of them catching and spreading covid as well. Instead, it stayed the same as they would still be limited by space available to them and by the simultaneous increase in activity from foxes (due to lower activity from people). This is the non-linearity: the change in food and domestic pet activity did not directly result in the rat population changing.

The small change of a few extra computers to work with with has led to a large change of projects running more and in a more effective manner as documents are more quickly produced and better formatted.

Domains of stability:

Complex systems are hostage to domains of stability. Effectively, this concept states that a given system can have more than one state in which it is stable. These change as the context does. By nature, complex systems gravitate towards those stable states, and will attempt to remain in them unless something external forces them out of it. These are usually binary concepts, with the ‘in-between’ being uncomfortable and sometimes chaotic.

An example of this is that a culture exists stably either with or without electricity, but the process of installation and education on what it is and how to use it is uncomfortable and unstable. As such, having electricity and not having it are domains of stability, the in-between moment is not.

The CSO is stable in its old state of ad hoc implementation, and in a new state of set processes and working practices. However the intermediary of changing ways of working causes instability and confusion in the system.

Tipping points:

Complex systems are often victim to this concept of a tipping point. These are thresholds such that once they are reached, the system goes through a rapid change into a different state. This state may be challenging to reverse.

House mess (especially those of us with children) is a great example of this. It starts slowly with a bit of clutter, and then rapidly speeds up into a total mess. As such, there is a tipping point at which the mess starts to spread rapidly.

The CSO members were slow to understand and take onboard new ways of working, but once enough had, it suddenly tips and had a ripple of rapid behaviour change.

Path-dependency:

This is a fairly intuitive concept, in that a complex system’s future depends on its history; how it got to its present state, and what that present state is currently. The order in which intervention activities are introduced affects their cumulative impact: what they add up to.

Evolution is the best example of a highly path-dependent process, as organisms cannot radically change from their predecessors. They change via mutations of existing adaptations, and the only way to understand their current state of being is to look at the history of mutations. To understand why a giraffe looks as it does, you need to look at the order of mutations that meant the species have incredibly long necks: a gradual series of changes over time. So, in this case, the giraffe’s long neck is path dependent – it wholly relied on that string of mutations to be what it is now. This path dependency is also why evolution often doesn’t find perfect solutions.

Similarly, an effective, well-led CSO will entirely depend on the process by which it got there. To understand the new order, you have to understand what activities happened at what point in time.

Openness:

Complex systems are often Open. This means that complex systems often have links and connections into other complex systems such that a change in a separate system can end up impacting a different one due to those links. Links could be information exchange, in/outflow of money or people, etc.

A good example of this corruption. Organised crime operates in its own sphere and system. However, if it is able to influence and bribe government officials, it is able to create disruption in the criminal justice system and change the way that system functions.

In our Terarian example, the CSO doesn’t operate in isolation. To understand why it implements ineffectively you have to understand the other organisations, authorities, and individuals that engage with it and contribute to the problem, such as angry citizens placing pressure on it, their own member turnover, or the flow of people through local authorities.

Change over time:

Finally, complex systems develop and change their behaviour over time. This is partly due to openness and adaptation of its components, but also because they are systems that are usually out of balance or unstable and therefore in a continuous process of change.

Social norms are excellent examples of this as customs and cultures radically change over time and can never be said to be at an end point. Covid-19 has led to a change in our social norms where more is happening online and people still work remotely or hybrid. We also cannot say this is the final state of our social norms

The CSO has shifted from a chaotic and inefficient to one that is more process-orientate and effective. However this is an interim state that is still in a process of change. We cannot say it is the final state.

(3) Juárez SP, Honkaniemi H, Heshmati AF, et al, Unintended health consequences of Swedish parental leave policy (ParLeHealth): protocol for a quasi-experimental studyBMJ Open 2021;11:e049682. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049682

Why is this relevant?

So those are your 11 features and a brief inro into what complexity is. The question may be ‘why should I care?’. This is relevant because whether working domestically or internationally we will be interacting with complex systems, because complex problems operate like that hive of bees. Just as the hive’s shape and structure is an emergent property of the arrangement of bees and their behaviours, a situation, problem, or issue that we are tackling is often the emergent property of a complex system of people or organisations interacting and reacting.

In terms of further resources, one of my current favourite discoveries are complexity weekends held by complexity adventures. Their website is a treasure trove of resources as well as fun ways to engage with others who are complexity curious. I also usually recommend that folk check out CECAN‘s work as I think they break down difficult concepts into excellent guidance and visuals. They and the Travistock Institute were behind the updates to the Magenta Book that help HMG organisations start to think about this more. I also highly recommend reading Donella Meadows’ work.