Behaviour Change

Guidance on accessible ways to think about behaviour change.

What is behaviour change?

Behaviour change itself, as a concept, feels nebulous and broad. That is largely because it is. Behaviour change asks questions about actors, actor groups, organisations or systems doing things differently. If a population isn’t washing their hands properly, how do we get them to start doing so? If a government is blocking change in a region, how do we stop it doing so? If – in the analogy I always use – I am not drinking tea, what needs to happen such that I do drink tea? While nothing I have to say here is new, I have often had teams say I explain behavioural science in very plain language and so wanted to capture that here in case it helps others. Please do read the original source material though, it is brilliant.

Behaviour change is thus an excellent example of complexity: it is hard to define exactly what the end result will look like, the pathway is highly intricate in terms of being hostage to environmental shifts, feedback loops, etc, and that you cannot repeat the process and get the exact same result.

As outlined in the Useful Theory of Change section, John Mayne1 tells us that Behaviour Change is that hinge point between where an intervention stops implementing and starts theorising. It is a key pivot point where we hope a given intervention has done enough to enable others to do things differently and see a series of change happen as a result of that.

However, it is a step that is far from simple and there are a multitude of models to help unpick and understand that, either at the design stage to plan an intervention, at the mid-point to identify emerging change, or retrospectively to evaluate how change came about. Personally, I am all about Susan Michie and the work done by the UCL Centre for Behaviour Change. The reasons for that are in the next section.

(1) Mayne, John. (2015). Useful Theory of Change Models. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation. 30. 10.3138/cjpe.30.2.142.

How do I do it?

As a result of this complexity, there are countless papers and models that attempt to get at this process: how to shift an actor or actor group from Behaviour A to Behaviour B.

As a starting point, I always refer people to Susan Michie’s Behaviour Change Wheel and the COM-B model.[2] The reason for this is because I have yet to find another model of behaviour change that doesn’t fit into this model. Motivation theories fit neatly into it, organisational maturity models fit into it, professional development models fit into it… you name it. This is in effect because the COM-B model is (in my eyes) a second-tier model that abstracts away from the detail of the components of behaviour, allowing those to fall into place below it. If you’ve found otherwise, I’m curious to hear what the situation was, but for now I’ll get into the details of this model with the recommendations that you read her papers.

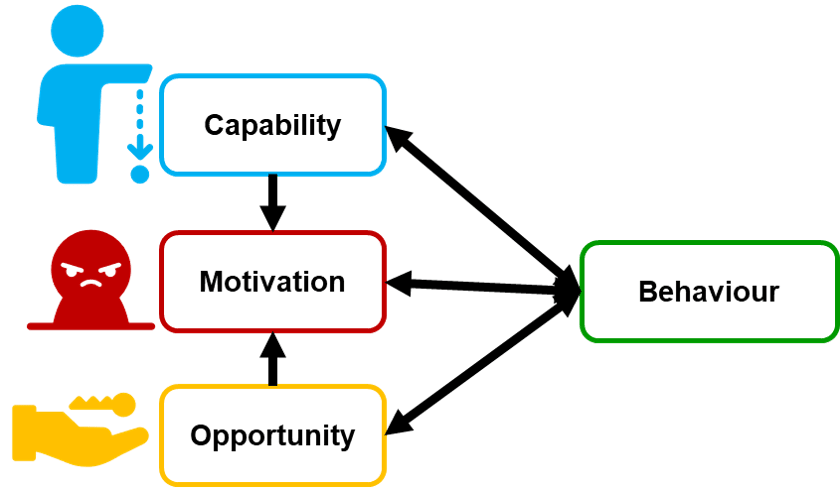

The COM-B model is relatively straight-forward and I’ve added a few explanatory flares based on my experience of what translates well, but I will touch on those once I’ve walked through the basic model. The idea is that behaviour can be understood as a combination of 3 aspects: Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation.

Capability is your individual ability to do something; it is about how your personal abilities interact with the world. (you -> world)

Opportunity is about your environmental enabling factors; it is about how the external world interacts with you. (world -> you)

Motivation is your internal will and desires; it is about how your most internal thoughts, habits, impulses, beliefs, and feelings interact with themselves; it is about how they interact with your interaction with the world, or how they interact with how the world interacts with you. (you -> you+world & you -> you+you)

These components break down further, as as so.

- Capability can be seen as having two components. Psychological ability: this is about intangible abilities, like knowledge and theory. Physical ability: this is about tangible abilities, like operating something, handling it, or even physically putting into practice an intangible ability (i.e. knowledge of how to operate a kettle channeled into physically plugging it in and turning on the switch. It is possible to have the psychological ability without the physical and vice versa.)

- Opportunity breaks down similarly. We have physical enabling or barrier factors, such as infrastructure, natural hazards, whether you live in a double landlocked country, whether you have certain things available to you and so on. We then also have the social enabling or barrier factors which are the intangible factors that externally affect us, such as cultural taboos, legislation, ways of working, standard operating procedures at work, and similar. Again, these can come apart. There might be a physical opportunity (i.e. access to natural resources) but no social opportunity to compliment it (i.e. a social taboo preventing me as a redhead accessing those natural resources). Equally, this happens in reverse where I might have the social ability to access something but no physical ability (e.g. I am socially allowed to drink raspberry tea but it is sold out in all supermarkets due to a supply chain breakdown).

- Motivation then breaks down as well. We have your reflective motivation, which can be considered as motivations we have learned or developed, such as reading something and coming to hold a belief. We then have your automatic motivations which are drivers that may not have been learned or could be less persuadable (things we might consider as governed by the lizard brain, as Kantar Public would put it), such as instincts, addictions, and habits. (Motivation is deeply complex and ultimately affected by the C and the O – I love this lecture by Robert West that unpacks the PRIME theory of motivation and how motivation gets build upon multiple things)

These are extremely useful frames to use to try to interpret why a current behaviour (or lack of behaviour) exists. I will also emphasize that these are just frames. There are some elements that are hard to categorise, and I encourage teams to not get overly hung up on how to categorise an observation (for example, lack of access to staff) and instead focus on its existence. Getting into an ‘is this a capability or opportunity’ debate often means you end up focusing on the wrong thing (much like the age old output/outcome debate). What matters is that you have identified something, and you are factoring it into your plans to create behaviour change.

Once you’ve identified the behaviour and the component reasons for its existence, you need to then use these to shift the behaviour into the new one. In effect, you will need to then need to change in terms of Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation. To explain this I have a bit of a silly example but I think it helps.

[2] Michie, S., van Stralen, M.M. & West, R., The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Sci 6, 42 (2011).

Michie S, Atkins L, West R. (2014) The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions. London: Silverback Publishing. http://www.behaviourchangewheel.com.

Let me make you a cup of tea…

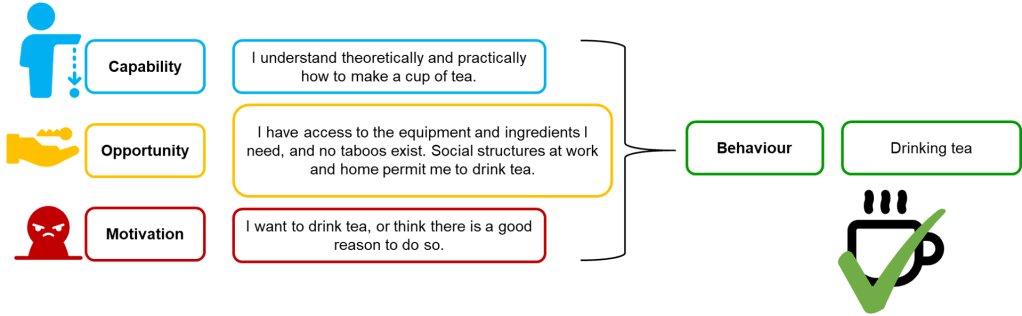

This might feel very overwhelming, and a lot to unpack. However, this really is very intuitive. I always explain this through the analogy of you trying to get me to drink tea.

Suppose my current behaviour is ‘not drinking tea’, and you want my future behaviour to be ‘drinking tea’, as this is a crucial step towards the direct benefit of positive British habits.

First, you must understand why I am not drinking tea – why are you seeing this behaviour?

Once those reasons are identified, you can understand how to change my behaviour: give me knowledge and skills, and/or physical access to the things I need, and/or break some social stigma (not quite so simple), and/or help me see the value in drinking it.

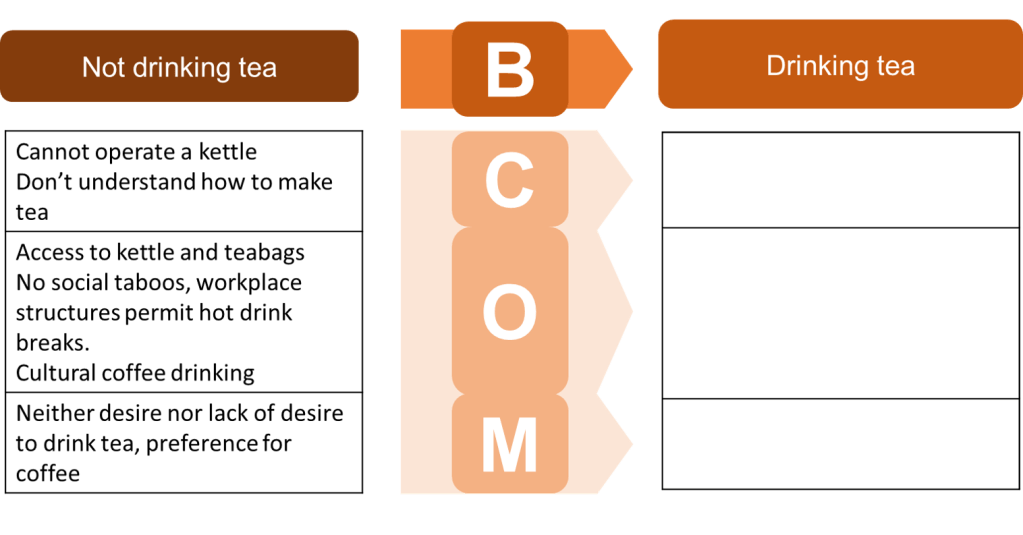

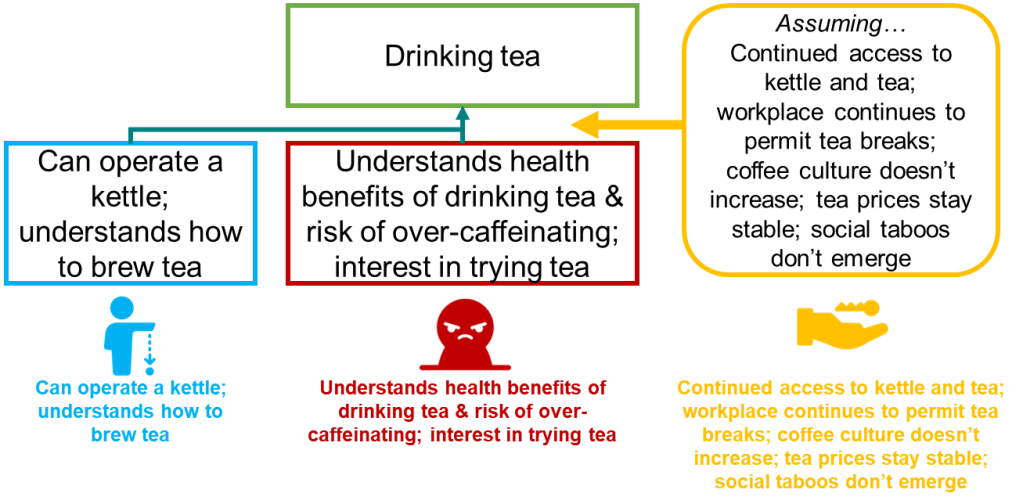

So, let’s say you asked all these questions about my not-drinking-tea behaviour and gained a bunch of information on what capabilities I may or may not have, what my opportunities are, as well as my motivations, and this is what you got.

Using this Change Frame model that I and others find helpful (it’s not mine! Credit to A Koleros and the ABC Framework3 (see references below)), you can then think about what might need to be the case to allow me to drink tea, as below:

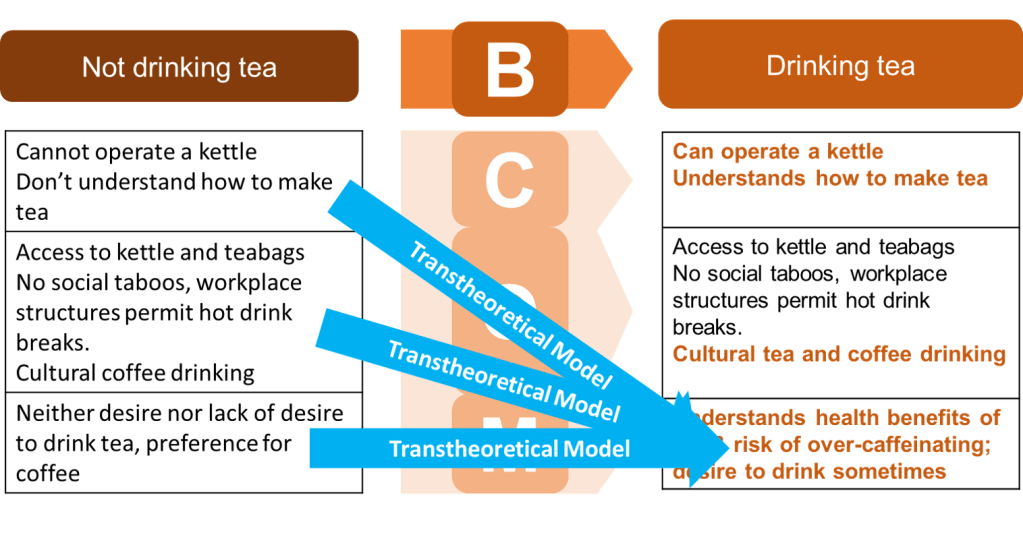

And, you know, based on those results you can see what has to change to get me to drink tea and identify what is in scope for your programme (i.e. of what needs to change, what you are able to change).

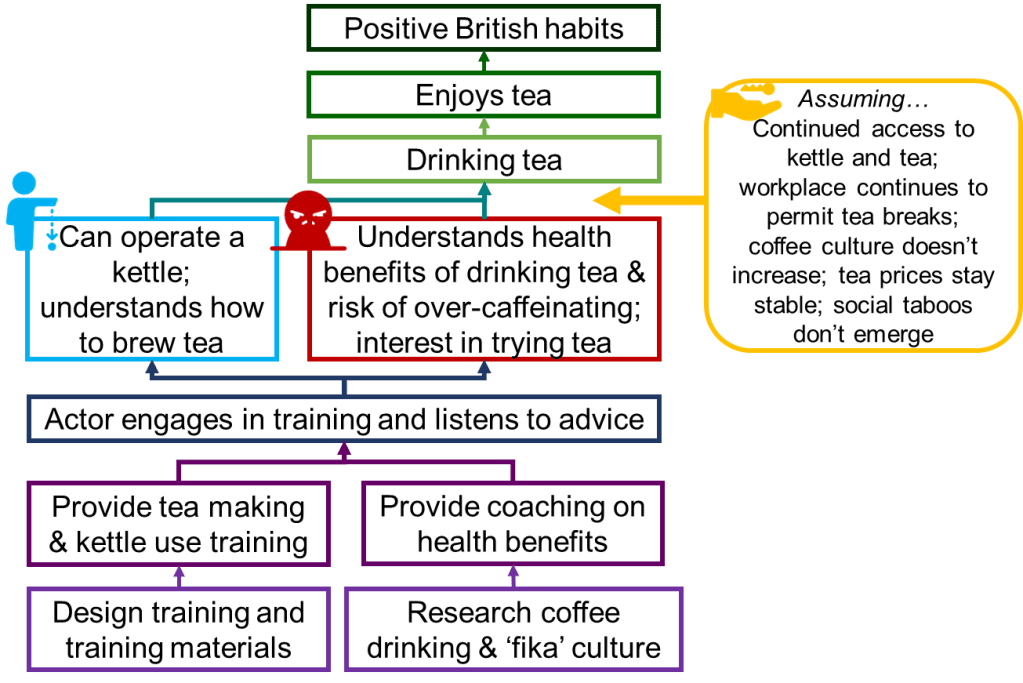

In this case, maybe you specialise in capacity building and coaching, and so what you can change is giving me the training and mentoring to change my capability and motivation. As such, what you can’t change would be the opportunity: giving me infrastructure and changing a culture. That gives you pathways and assumptions immediately for what behaviours need to change in your target groups! Neat, huh? This gives the foundations of what’s called a Theory of Action: like a mini theory of change for how to bring about behaviour change in target groups. (This is inspired by how Actor-Based Change Frameworks connect behaviour change to theories of action)3

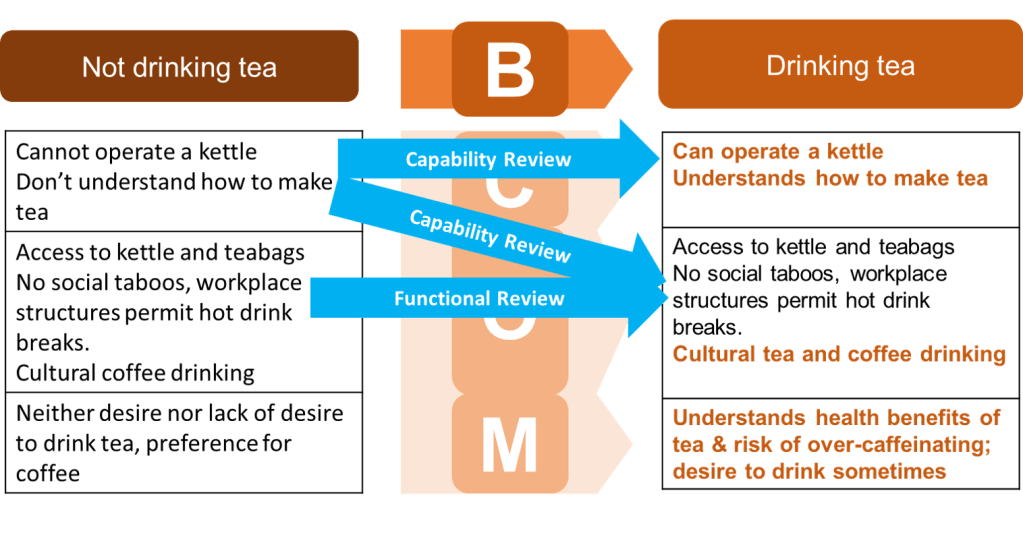

Based on what is in scope, the COM-B change here will look like this:

This is because the opportunities are not changeable. In this example, this is because most of these are opportunities that must not change, such as the lack of social taboo and the current price of tea. However, we also identified earlier that there is something that you cannot change, namely the coffee culture I was brought up with and that exists in Sweden. As such, these kinds of factors also will end up in this little assumptions box. In those cases, this is a scenario where we are saying either (i) we think we can create a behaviour change despite not being able to change everything (e.g. not changing an attitude), or (ii) we are hoping something/someone else will change this factor. In situation (ii) this is a great opportunity to phone a friend and see if another intervention can tackle the out-of-scope items but I digress…

What I find helpful in the next step is thinking about how to bring about those capability and motivation changes. Now, this is where it gets interesting. COM-B helps you break down what is needed for change, but doesn’t tell you how to do it. This is where other models can come into play.

If you needed to shift a motivation, this is where something like the PRIME theory of motivation (see link above) or other theories like the transtheoretical model[4] can slide into the COM-B framework:

Or shifting workplace situations (opportunity) could be understood through an organisational maturity model:

Or, even, activity approaches or processes might be what’s needed to shift to a given opportunity, and those can be slotted in as well:

The list goes on. COM-B just helps you get to grip with what needs to change to see a new behaviour. This then helps you identify a) what is in scope, and then b) think about how you can bring about those changes such that a new behaviour follows.

In this case, we have a rudimentary example, and as such it may be that based on prior experience, your Political Economy Analysis, learning from others who have worked with me, etc, that you know some training and coaching will reach me well, I will listen, and then the behaviour change occurs as follows. This is your Theory of Action!

This then slots into your overall Useful Theory of Change as so:

As such, behaviour change doesn’t need to be nebulous and scary. There are ways of breaking it down into bitesize steps that also acknowledge the complexity of what you are dealing with.

[4] Prochaska, J. O., Johnson, S., & Lee, P. (2009). The Transtheoretical Model of behavior change. In S. A. Shumaker, J. K. Ockene, & K. A. Riekert (Eds.), The handbook of health behavior change (p. 59–83). Springer Publishing Company.

West R (2007) The PRIME Theory of motivation as a possible foundation for addiction treatment. In J Henningfield,

P Santora and W (Eds) Drug Addiction Treatment in the 21st Century: Science and Policy Issues. Baltimore: John’s

Hopkins University Press.

[2] Koleros, A., Mulkerne, S., Oldenbeuving, M., & Stein, D. (2020). The Actor-Based Change Framework: A Pragmatic Approach to Developing Program Theory for Interventions in Complex Systems. American Journal of Evaluation, 41(1), 34–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214018786462

I need help

While the explanation may be simple, putting this into practice may feel quite challenging. I highly recommend reading the papers and references that I have cited to further outline your understanding of these models. Motivation is the most interesting and difficult piece to shift, so I highly recommend looking into Robert West’s work on that.

Ultimately, a programme designed with a good theory of how to bring about behaviour change in its target groups (‘theories of action’) is significantly more likely to succeed, and be able to adapt in the face of adversity.

There are a lot of talented people who use these approaches working as independent consultants; I am always happy to recommend people as needed!